Two New Names: should Mauer and Wright go to the Hall of Fame?

If only the ballot had some sort of criteria, we could know for sure.

To be clear, first of all—David Wright shouldn’t be a Hall of Famer at all. He didn’t play long enough, and his peak was not high enough. It’s one thing when a player has an incredible 7 year peak of true greatness, and in a future piece I plan to talk about one such player—Cliff Lee—but Wright was never considered the best player in the game, the best position player, and never won nor deserved an MVP.

But Wright will inevitably make it. He checks all the non-statistical boxes. Beloved personality? Check. Franchise legend? Check. Played for a big-market team? Major check! Wright through the age of 30 was basically Derek Jeter, but without the postseason success. Incidentally, I’m not going to talk about postseason success, or the lack thereof. Leaving aside that it’s objectively ridiculous to judge a baseball player’s individual accomplishments based on the quality of team they played on, there has actually been a trend in recent years to consider players more rationally. Not that nowadays all their choices totally make sense.

Sidebar: this is your annual reminder that Harold Baines is in the Hall of Fame. Harold Baines played 21 seasons, and compiled 38.8 WAR. Both Mauer and Wright played 14 seasons, and Mauer has 55.2 WAR and Wright has 49.2. Also, Harold Baines best-ever season was 4.3 WAR, which is below the 5 WAR threshold that is considered “All-Star caliber.” Not only was he not great, he was never even really…good. But he’s in because OOHLALA those counting stats. Now I promise I will not bring this up again until next year.

I’m writing this piece because of the striking similarities between Mauer and Wright. Both debuted in 2004, and both retired after the 2018 season. Both were media favorites—although of course, Wright was a New York media favorite, which is a whole different jar of tomatoes. Both spent their entire careers with the team that drafted them, and rank among the most recognizeable players from that team’s recent history. Neither ever won a World Series, though of course Wright played in one in 2015 and Mauer never came close.

And then there’s the really big similarity: both players were felled before their time by the IL monster. On Wright’s BRef page, there’s an obvious divider at 2012, when Wright was 29. Before, he averaged 140 games per season. From there to his final real season in 2016, he only appeared in 80 games a year.

David Wright

Wright came up as a third baseman and remained there his entire career. He was never considered an especially strong defender—draft profiles from the early ‘10s note derisively that its a good thing defense doesn’t matter in fantasy. He did win two Gold Gloves, but these were in seasons when he made 16 and 21 errors. Using Sean Smith’s Total Zone score, David Wright finished his career at -68 Total Zone, which, in case you aren’t familiar, is bad. Add these to the long list of defensive accolades won for offensive prowess in baseball history. In fairness, however, Wright was widely considered a smart player and had an above-average arm that didn’t fail him until late in his career.

And of course, defense was not why Wright was on the field. Rather than looking at career totals, let’s look first at Wright’s best seasons and acknowledge why this guy is on the Hall ballot at all:

David Wright, 2005-2012

.301/.384/.505/.888, 136 OPS+

Average Season: 20 SB, 24 HR, 38 doubles, 121 strikeouts

Pretty impressive. In 2023, Wright looks like a Moneyball dream—plays a valuable position well enough, gets on base a ton, pops XBHs. He’s the sort of player who would have gone wildly underappreciated if he had played in a different city or debuted ten years earlier.

Wright’s HOF case cannot rely on his 242 career homers, but it is supported by his remarkably consistent XBH totals. His year by year totals, in this area at least, are very similar to Ryan Braun or Chase Utley:

Wright, Doubles 2005-2014

42,40,42,42,39,36,23,40,23,30

Chase Utley, a similar player in many ways, compiled 411 doubles, playing until he was 39. Playing only until 33, Wright compiled 390. He was a total base machine.

Joe Mauer

Mauer debuted in 2004 as the Twins catcher; local boy, top prospect, wunderkind. It is worth noting that while Wright was equally beloved in New York, he actually outperformed expectations and became a folk hero, whereas Mauer came up as the Chosen Heir. He was taken as the 1-1 in ‘01, despite the consensus No.1 being Mark Prior, undoubtedly a ready-made ace. Prior appeared in 5 seasons, pitching his last Major League game at 25. With the Twins coming off the late nineties—perhaps the most futile period in their history—Mauer was viewed, fairly or not, as a franchise savior.

To be clear, this wasn’t unwarranted—Mauer was a dumbfounding hitting talent. The Twins knew they were onto something remarkable when that season at Elizabethtown High A, he batted .400 in 32 games, striking out only ten times. In his first full season, Mauer batted .294/.372/.411, though with an unimpressive 9 home runs. If Robinson Cano had not been a Yankee, Mauer would have cruised to the Rookie of the Year award.

It’s worth saying that from the very beginning Mauer was considered a plus defensive catcher, one 2002 ESPN scouting report raving,“he’s a better athlete than most shortstops.” Despite his elongated frame, Mauer could pivot, slide, and pop to his feet with ease—the same report proved correct several times over in its assessment that he would become a Gold Glove defender. His overall defensive contribution of 40 TZ is well above average. For context, AJ Pierzynski played in the same division in the same time frame; he played catcher much longer than Mauer; his TZ is -35. His arm was feared by baserunners the world over. Mauer’s 36% career caught-stealing rate is better than Salvador Perez (34%) and Buster Posey (33%). In 2007, only 21 runners stole a base from Joe Mauer, but he nailed 24 (53%). In 2013, his final year behind the plate, Mauer nailed 43% of runners.

But this is all just gravy on the true Hall of Fame case, which Mauer made using the prettiest swing in baseball. People rave about the gorgeous swing of Mookie Betts and Mike Trout, but both exceed 100 strikeouts every year. Mauer’s swing was beautiful not just because of how it looked, but how it seemed able to connect squarely with just about any strike a pitcher could throw. His peak years were littered with the crushed caps of pitchers who threw them into the dirt in frustration, because Joe Mauer had lined their perfect breaking ball into the opposite field. Mauer was probably the second-best opposite field hitter of his generation (because, Ichiro).

The raw numbers are impressive: career .306/.388/.439, 2123 hits, 428 doubles, and of course the 143 home runs, so maligned during his career. I heard a radio host one time observe that there isn’t any obvious reason why Mauer was criticized for his lack of power—after all, there are many well-respected stars without pop. However, the host hypothesized—and this sounds plausible to me—that Mauer’s massive 6’5” frame simply looked powerful, and this led non-Twins fans to assume his lack of home run power was a fault.

The idea that Mauer was less productive due to low power numbers, however, does not hold up to scrutiny. Using the Play Index, I found every player who’s logged 900 games at catcher, post-’47, and sorted them by OPS. Of 110 catchers, Mauer ranks seventh, ahead of Johnny Bench, Pudge-Rod, Carlton Fisk, and Brian McCann. The only moderns ahead of him would be Buster Posey, who will waltz into the Hall of Fame, and Jorge Posada, whose stats are inflated but has an interesting Hall case himself.

For as much as Mauer declined in the last third of his career, this stat remains remarkable: only once, in injury-ridden 2015, did he strike out 100 times. His frequent rival for batting titles, Derek Jeter, did this 9 times. Six different times, Joe walked more than he struck out for a full season. David Wright struck out 100 times seven times, including a monstrous 161 times in 2010.

Best Season

The best all-around catcher season ever was Johnny Bench’s 1972 (his age-24 season). His BRef WAR was 8.6, with 2.4 being defensive. Yes, I know Mike Piazza put up 8.7 WAR in 1997, but 1) he was a mediocre defender, and 2) I have long felt that bWAR does not make enough of an adjustment for the steroid era.

Sidebar: according to BRef, between 1995 and 2005 there were 37 player-seasons of 8+ WAR. Between 2013 and 2023, there were 16. On the same intervals, there were 17 seasons of 9+ WAR (1995-2005) and only 7 (2013-2023). If bWAR is supposed to represent relative value, these numbers should be close to even. The steroid era’s numbers are twice as big. Yes, that was an offense-dominated time and this is a pitching-dominated time, but that shouldn’t matter. WAR is normalized based on the run-scoring environment. Hence, I’m suspicious of their methodology.

If you have Stathead cook up a list of every catcher season of 100 games or more and sort by WAR ( in the Integration Era), Piazza’s 1997, Gary Carter’s 1982, and Bench’s ‘72 and ‘74 are the top 4.

Fifth is Joe Mauer’s 2009, in which he won the sabermetric triple crown, leading the league in batting (.365), on-base (.444), and slugging (.587). Yes, Joe Mauer did lead the league in slugging, and yes, that is the only time a catcher has ever done that. Also, he walked more than he struck out, logged 307 total bases, and generally won the MVP deservingly (actually, he took all but one first place vote, with one being left blank [screw you] and one being oddly cast for Miguel Cabrera).

Now, David Wright. The best season of David’s career, by both WAR and the eye test, was 2007, which was that particular variety of standout year that never quite wins MVP because it’s too uniformly excellent to even be interesting.

David Wright, 2007

.325/.416/.963, 149 OPS+, 30 HR, 34 SB, 42 doubles, 330 TB

All-Star, Silver Slugger, Gold Glove

None of these numbers are individually eye-popping, but taken together, they’re quite impressive. To indulge in a bit of cherry-picking, I asked Stathead to list every player-season since Integration with 30 home runs, 30 steals, and a .400 on-base percentage. You might be surprised to learn it’s only been done 18 times by 12 players. Ronald Acuna Jr. did it this year. Mooke Betts did it in 2018. Jeff Bagwell managed it twice. Barry Bonds did it 5 separate times. David Wright’s 2007 is on this list. Players like Rickey Henderson, Mike Trout, and Mickey Mantle never did this. But David Wright did, and he did it playing in 160 games.

It’s a little sad, looking at it now, that early in his career one of Wright’s best qualities was his durability—even if he wasn’t among the very best players in the game, everyone lauded him for always being there and consistently producing, day in and day out.

In Context

I think I’ve made the case pretty convincingly that Mauer’s career should be viewed in a completely different light given that he was a catcher for so much of it (although, incidentally, Mauer was the best defensive first basemen in the AL in 2013 and 2014, and got zero attention for it). If Mauer had retired when his catching career ended in 2013, his career batting average would be .323, rather than the .306 he retired at. This may seem like splitting hairs, but consider: in the first eleven seasons of Ichiro’s career, he batted .322, and like Mauer, he kept playing, eventually retiring at .310. Yet no one questions Ichiro’s greatness, while Mauer’s .306 is viewed as a knock on him. In reality, the .323/.405/.873 career mark as a catcher is alone probably worthy of Coopertown.

Mauer being a catcher should change everything about the discussion. His overall numbers are similar to Victor Martinez (another feared line-drive hitter with a borderline HOF case) but with the key difference that Mauer played the premium position. It’s not that anybody is trying to discredit Mauer, but it seems as though national writers often remember Mauer as a good hitter with middling counting stats, and forget that everything he did was more valuable because of his position. Remember, Mauer won three AL batting titles. He remains to date the only AL catcher to ever win even one.

When you consider both the offensive and defensive accolades seen above, it’s almost inescapable that Mauer was the best catcher of his generation. The only serious competition would be Yadier Molina or Buster Posey. Here’s the basic breakdown, including JAWS, which is a BRef stat designed specifically to determine Hall of Fame likelihood.

Joe Mauer | 55.2 career WAR, 47.1 JAWS, 124 OPS+, 40 TZ, .388 OBP

Yadier Molina | 42.1 WAR, 35.5 JAWS, 96 OPS+, 163 TZ, .327 OBP

Buster Posey | 44.8 WAR, 40.7 JAWS, 129 OPS+, 77 TZ, .372 OBP

Wright, on the other hand, was not conclusively the best third baseman of his time. That would have to be Adrian Beltre. However, counting only players whose career began after 2000, David Wright is the fourth-best 3B by WAR, behind Evan Longoria, Manny Machado, and Nolan Arenado. Evan Longoria has an interesting borderline Hall of Fame case in his own right, and the other two are on a Hall track at the moment, but not nearly done yet. However, if you sort the same list by Offensive WAR only—not that I believe defense doesn’t matter, but some think that way—Wright ranks first. Granted this is an arbitrary sample, but indulge me one more: if you arrange these third basemen by OPS+, the only player ahead of Wright is Alex Bregman, who’s short career is unfinished. Incidentally, if Bregman (29) retires at age 35 with the same OPS+ he currently sports, he will walk into the Hall on the first ballot—he’s been really, really good so far in his career.

To pick a slightly less arbitrary cutoff, let’s look at career peaks. Stathead, in which I place my abiding trust, actually failed me here, since it does not have a filter for 7-year peak—so I just looked at all Integration Era third basemen during the years that constituted Wright’s peak (22-29). I admit this is not very scientific, since not all players peak in these years—but at least it is apples-to-apples. On this list of more than 170 player careers, Wright’s age 22-29 stretch is the tenth best by WAR. Every one ahead of him is in the Hall or still active.

I think given this information, it is at minimum fair to say that since the end of the steroid era, David Wright is among the three best offensive third basemen around. His peak was higher than Scott Rolen (recently voted in) and his 20s were as good as Nolan Arenado, Manny Machado, and Jose Ramirez.

But that’s sort of the end of it. Wright was a very, very good hitter for a relatively short time. He was never a good defender, and was never the best player at his position. His career was ended early by injuries, but what we did get to see of fully functional Wright was not crazy enough to qualify for the informal Sandy Koufax Rule the Hall voters seem to recognize for great players with short careers. Wright is not a Hall of Famer—but it was the steep dropoff he saw in his numbers that seals that. Had his age 30-33 seasons remained good—not even great—he’d probably have a strong case.

Mauer, on the other hand, would almost certainly qualify as a Sandy Koufax figure if he had retired rather than moved to first base. The move to first has bizarrely tarnished his legacy, even though he was a good defender there, and hit well above average for several more seasons.

But it seemed like a letdown, because that first decade was unreal: 3 batting titles, a well-deserved MVP, elite defense, and one of the highest on-base rates of his era, all from the catcher position. Had Mauer simply walked away at age 31, he would have been revered and no one would have hesitated to project that greatness onto his imagined next decade, absolving him, as it were, for his lack of longevity.

By any reasonable measure, Mauer is the greatest catcher of this century, and forgetting his position, one of the greatest pure hitters of his age. He is in a conversation of five or six for the title of best offensive catcher ever, his only disadvantage being his lack of power.

Wright is not a Hall of Famer, just a very good player who will be fondly remembered by Mets fans. Though their careers had different arcs, he is quite a bit like Jimmy Rollins, who was among the best at his position for many years and will likely remain a hero to Phillies fans forever, but doesn’t belong in the Hall either. Mauer is a Hall of Famer. You can’t tell the story of baseball and not include the best pure hitter to ever catch.

UPDATE

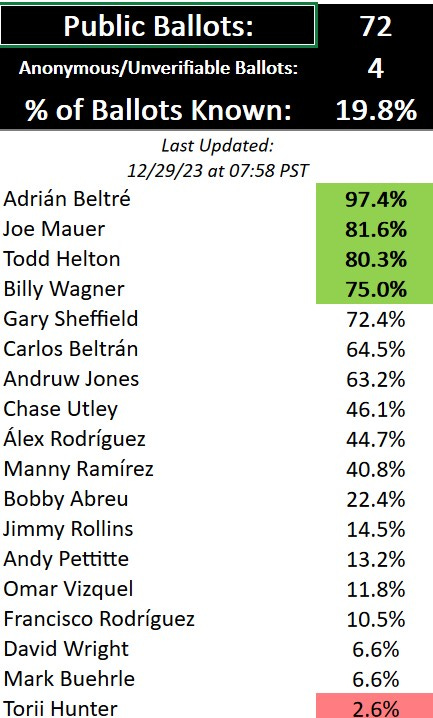

While I was working on this piece, I was directed to Ryan Thibodaux’s Baseball Hall of Fame tracker, which helpfully collates all the ballots which have been made public (which, for my money, should be required of the BBWAA). This is of course not conclusive, since it’s essentially like exit polls, but check out the progress of our heroes: